We all look to our past to define our present, but we don’t always realize that our view of the past is shaped by subsequent events. It’s easy to forget that the Dutch dominated the world’s oceans and trade in the seventeenth century when our cultural imagination conjures up tulips and wooden shoes instead of spices and slavery. This book examines the Dutch so-called “Golden Age” though its artistic and architectural legacy, recapturing the global dimensions of this period by looking beyond familiar artworks to consider exotic collectibles and trade goods, and the ways in which far-flung colonial cities were made to look and feel like home. Using the tools of art history to approach questions about memory, history, and how cultures define themselves, this book demonstrates the centrality of material and visual culture to understanding history and cultural identity.

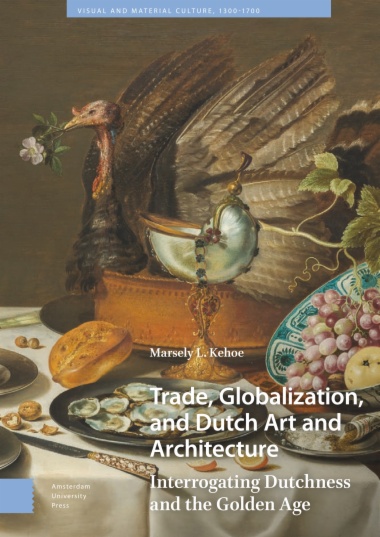

- Cover

- Table of Contents

- 1. Introduction: Grasping at the Past

- Dutch and Dutching: Hybridity and Decolonization

- Collective Identity, Memory, Forgetting, and Innocence

- The Importance of Material Culture and Art History to Tell This Story

- Global Dutch Art History

- Chapter Outline

- Dutch Identity in Conflict

- Works Cited

- 2. The Gilded Cage: Dutch Global Aspirations

- The European Age of Discovery

- Establishment of the Dutch Republic

- The Beginnings of Dutch World Exploration and the Foundation of the VOC

- The Dutching of the Nautilus Shell

- Dutch Nautilus Mounts and the Dutch Sea

- The Freedom of the Seas

- The Formation and Fate of the WIC

- Guarding “Free Trade”

- The Twelve Years’ Truce

- The Denouement of the Republic and Transition to Monarchy

- Delft and the Shifting Legacy of the “Golden Age”

- Works Cited

- 3. Gathering the Goods: Dutch Still Life Painting and the End of the “Golden Age”

- Dutch Still Life: Defined by Objects

- Representing Objects in Dutch Still Life

- Pepper in Still Life and Trade

- Dutching Still Life

- Tables

- Works Cited

- 4. Dutch Batavia: An Ideal Dutch City?

- The Founding of Batavia

- The Plan of Batavia

- A Dutch City in the Tropics

- Dutch City Planning Principles in the Seventeenth Century

- Hierarchy in Batavia

- Ordering Batavia’s Population

- Conclusion

- Works Cited

- 5. Simplifying the Past: Willemstad’s Historic and Historicizing Architecture

- The Founding of Willemstad and the WIC

- The Vernacular Architecture of Downtown Willemstad

- The Townhouse as Dutch Colonial Architecture

- The Curaçaoan People

- Tracing Change over Time

- Conclusion

- Works Cited

- 6. Conclusion: The “Golden Age” Today

- Works Cited

- Archives and Databases

- Bibliography

- Acknowledgements

- Index

- List of Illustrations

- Colorplates

- Plate 1: Nicolaes de Grebber (mount, attributed), Nautilus Cup, 1592. Collection Museum Het Prinsenhof, Delft, Netherlands. Nr. PDZ3. Nautilus shell with gilt silver. Purchased with the support of the Vereniging Rembrandt. Photograph Albertine Dijkema.

- Plate 2: Cornelis Bellekin (shell, attributed), Anonymous nineteenth-century Danish smith (mount), Nautilus Cup with Genre Scenes, ca. 1660. Nautilus shell with gilt silver. KODE Art Museums and Composer Homes, Bergen, Norway. Inv. nr. VK 5022.

- Plate 3: Anonymous Dutch engraver (attributed, shell), Andreas I. Mackensen (mount), Nautilus Cup, first half seventeenth century (attributed, shell), 1650–1660 (mount). Nautilus shell and gilt silver. Kunstgewerbemuseum Staatliche Museen, Berlin, Germany. Inv. Nr. 1993.63. Photograph BPK Bildagentur / Saturia Linke / Art Resource, NY.

- Plate 4: Willem Kalf, Wineglass and a Bowl of Fruit, 1663. Oil on canvas. Cleveland Museum of Art, USA, Leonard C. Hanna, Jr. Fund. 1962.292.

- Plate 5: Jan Davidsz de Heem, Still Life with Nautilus Cup and Lobster, 1634. Oil on canvas. Staatsgalerie, Stuttgart. Inv. Nr. 3323. Photograph Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY.

- Plate 6: Willem Kalf, Still Life with a Porcelain Pitcher, 1653. Oil on canvas. Alte Pinakothek, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Munich, Germany. Inv. nr. 17. Photograph BPK Bildagentur / Art Resource, NY.

- Plate 7: Andries Beeckman, The Castle of Batavia, 1661, oil on canvas. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. SK-A-19.

- Plate 8: Handelskade, Willemstad, Curaçao, 2014. Photograph author.

- Figures

- Figure 2.1: Pieter Claesz, Vanitas Still life with Nautilus Cup, 1636. Oil on panel. Westphalian State Museum of Art and Cultural History, Münster, Germany. Inv.-Nr 1369 LM. Photograph BPK Bildagentur / Hanna Neander / Art Resource, NY.

- Figure 2.2: Jan Jacobsz. van Royesteyn (mount, Dutch, 1549–1604), Nautilus Cup, 1596. Silver-gilt and nautilus shell, H. 11 3/8 in. (28.8 cm). The Toledo Museum of Art, purchased with funds from the Florence Scott Libbey Bequest in Memory of her Father, M

- Figure 2.3: Nautilus Emblem, Nr. 49 in Joachim Camerarius, Symbolorum et emblematum ex aquatilibus et reptilibus (Nuremburg: 1604). Photograph Newberry Library, Chicago, USA.

- Figure 2.4: Jeremias Ritter (mount), Nautilus Snail, ca. 1630. Nautilus shell and silver-gilt. Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut, USA. Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan. 1917.260. Photograph Allen Phillips/Wadsworth Atheneum.

- Figure 2.5: Anonymous Rotterdam silversmith (mount), Nautilus Cup, ca. 1590. Nautilus shell, gilt silver, jewels, and remnants of paint. Collection Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, Netherlands. Inv. nr. MBZ 185 (KN&V). Loan: Rijksdienst voor het

- Figure 2.6: Anonymous engraver (shell), after Rembrandt van Rijn, anonymous silversmith (mount), Nautilus Cup, after 1631. Nautilus shell and gilt silver. Ostrobothnian Museum, The Karl Hedman Art Collection, Vaasa, Finland. Photograph Markus Paavola.

- Figure 2.7: Anonymous engraver, Guangzhou, China (attributed, shell), Anonymous German and Italian silversmiths (mount), Nautilus cup, ca. 1550 (attributed). British Museum, London, England. WB 114.

- Figure 2.8: Jörg Ruel (mount), Nautilus Boat, ca. 1610–1620. Nautilus shell and gilt silver. Grünes Gewölbe, Dresden, Germany. Inv.Nr. III. 152. Photograph Paul Kuchel.

- Figure 2.9: Joachim Hiller, Nautilus Ostrich, ca. 1600. Nautilus shell, gilt silver, jewels, ivory, and painting. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. BK-1958-44.

- Figure 2.10: Display in Amsterdam Museum, 2009. Photograph author.

- Figure 2.11: Franciscus Leonardus Stracké, Monument to Hugo Grotius, 1886. Delft, Netherlands. Photograph author.

- Figure 2.12: Display in Museum Het Prinsenhof, 2009. Photograph author.

- Figure 3.1: Willem Claesz Heda, Breakfast Still Life, 1637. Oil on wood. Louvre, Paris, France. INV1319. Photograph Gérard Blot. © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY.

- Figure 3.2: Abraham van Beijeren, Banquet Still Life, ca. 1660s. Oil on canvas. Hohenbuchau Collection, Liechtenstein Museum, Vienna, Austria. Inv.: HB 23. © Liechtenstein Museum / HIP / Art Resource, NY.

- Figure 3.3: Abraham van Beijeren, Still Life with Lobster and Fruit, early 1650s. Oil on wood. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA. 1971.254.

- Figure 3.4: Willem Kalf, Still Life with Nautilus Cup, 1662. Oil on canvas. © Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, Spain. 1962.10.

- Figure 3.5: Willem Claesz Heda, Nautilus Cup and Plates with Oysters, 1649. Oil on wood. Staatliches Museum, Schwerin, Germany. Inv. nr. G68. Photograph BPK Bildagentur / Elke Wolford / Art Resource, NY.

- Figure 3.6: Willem Claesz Heda, Still Life with Oysters, a Silver Tazza, and Glassware, 1635. Oil on panel. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA. 2005.331.4.

- Figure 3.7: Pieter Claesz, Still Life with a Turkey Pie, 1627. Oil on wood. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. SK-A-4646.

- Figure 3.8: David Davidsz de Heem, Still Life, ca. 1668. Oil on canvas. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. SK-A-2566.

- Figure 3.9: “Generale Carga,” 1690. Nationaal Archief, The Hague, Netherlands, Archief van Johannes Hudde (1628–1704), archive nr. 1.10.48, inventory nr. 17. Photograph author.

- Figure 3.10: “Generale Carga.” Hollande Mercurius 41 (1690) (Haarlem: Pieter Casteleyn), 336. Photograph Newberry Library, Chicago, USA.

- Figure 3.11: Artus Quellinus I and workshop, The Four Continents Paying Homage to Amsterdam, design for the back pediment, Amsterdam Town Hall (now Royal Palace), ca. 1665. Terracotta. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. BK-AM-51-3.

- Figure 3.12: Willem Kalf, Still Life with a Nautilus Shell, 1643. Oil on canvas. Musée de Tessé, Le Mans, France. Inv. LM10.89. Photograph Agence Bulloz. © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY.

- Figure 3.13: Willem Kalf, Still Life with Columbine Goblet, ca. 1660. Oil on canvas. Detroit Institute of Arts, USA. Founders Society Purchase, General Membership Fund, 26.43.

- Figure 4.1: Aelbert Cuyp, The Commander of the Homeward-Bound Fleet, ca. 1640–1660, oil on canvas. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, Netherlands. SK-A-2350.

- Figure 4.2: Jacob Coeman, Pieter Cnoll, Cornelia van Nijenrode, Their Daughters, and Two Enslaved Servants, 1665, oil on canvas. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, Netherlands. SK-A-4062.

- Figure 4.3: Waere affbeeldinge Wegens het Casteel ende Stadt Batavia, 1681. Nationaal Archief, The Hague, Netherlands. 4.VELH Kaartcollectie Buitenland Leupe, supplement, nr. 430.

- Figure 4.4: Plan van ‘t fort en omleggende land Jacatra, detail, 1619, manuscript. Nationaal Archief, The Hague, Netherlands. 4.VEL Kaartcollectie Buitenland Leupe, nr. 1176.

- Figure 4.5: Jacob Cornelisz Cuyck, Plan of Batavia, 1629, copy by Hessel Gerritsz, 1630, manuscript. Nationaal Archief, The Hague, Netherlands. 4.VEL Kaartcollectie Buitenland Leupe, nr. 1179B.

- Figure 4.6: Plan der Stad en ‘t Kasteel Batavia. Made under the direction of P.A. van der Parra in 1770, printed in Amsterdam by Petrus Conradi in 1780. Leiden University Library, Netherlands, Digital Collections. COLLBN Port 57 N 50.

- Figure 4.7: Carte de l’isle de Iava ou sont les villes de Batauia et Bantam, detail, ca. 1720, watercolor. Newberry Library, Chicago, USA.

- Figure 4.8: Seventeenth-century houses in Batavia, on the Spinhuis Gracht, photograph ca. 1920. Leiden University Library Digital Collections, Netherlands. KITLV 88700.

- Figure 4.9: Johannes Nieuhof, Tijgersgracht, 1682. Johannes Nieuhof, Gedenkwaardige Brasiliaense zee- en landreis (Amsterdam: Widow of van Jacob van Meurs, 1682), between 198–199. Columbia University Libraries, USA.

- Figure 4.10: Simon Stevin, Ideal Plan for a City, 1650. Simon Stevin, Materiae Politicae. Bvrgherlicke Stoffen: vervanghende ghedachtenissen der oeffeninghen des doorluchtichsten Prince Maurits van Orangie (Leiden: Justus Livius, 1650). Newberry Library,

- Figure 4.11: A. Besnard after Daniël Stalpaert, Map of Amsterdam with plan for the Fourth Expansion, ca. 1663–1682. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. RP-P-AO-20-33.

- Figure 4.12: General Population Distribution of Batavia. Author’s alteration of Figure 4.3.

- Figure 5.1: Handelskade 1 (left) and Handelskade unnumbered (right), details. From left: 1885, photograph Soublette et Fils (Collection Nationaal Museum van Wereldkulturen, Netherlands. Coll.nr. TM-60028720); 1915, photograph Soublette et Fils (Collection

- Figure 5.2: Gerard van Keulen, Map of Curaçao, 1716. Library of Congress, Washington, DC, USA.

- Figure 5.3: J. Stanton Robbins & Co. / Blair Associates, The Distinctive Architecture of Willemstad, April 1961. From The Distinctive Architecture of Willemstad: Its Conservation and Enhancement. A Report prepared by J. Stanton Robbins and Lachlan F. Blai

- Figure 5.4: Entrance to the St. Anna Bay. Photograph Soublette et Fils, 1890–1895. Thomas Frederick Davis papers, Descriptive account of Curaçao, Netherlands Antilles, 1902, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, USA. mm 80003197.

- Figure 5.5: Penha Building (Heerenstraat 1), details. From left: 1800 (‘t Eÿland Curacao, manuscript. Library of Congress Geography and Map Division, Washington, DC, USA. G5181.A35 1800 .E9.); ca. 1822 (R. F. Raders, De haven van Curaçao, acquatint, New Y

- Figure 5.6: Warmoesstraat, Damrak, Amsterdam. ca. 1880–1890. Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed, Netherlands. OF-05129.

- Figure 5.7: Late nineteenth-century Scharloo houses. Left: Villa Maria, 2–6 N. van den Brandhofstraat, built 1885, photograph ca. 1888–1900, Soublette et Fils, detail. (Collection Nationaal Museum van Wereldkulturen, Netherlands. Coll.nr.: TM-60060208). R

- Figure 5.8: Plantation house Groot Santa Martha with kunuku huts, detail, ca. 1900, photograph Soublette et Fils. Collection Nationaal Museum van Wereldkulturen, Netherlands. Coll.nr. TM-60019497.

- Figure 5.9: View of Willemstad, the Harbor of Curaçao, 1780, drawing and watercolor. Collection het Scheepvaartmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Inv. nr. S.0163.

- Figure 5.10: Whimsical Curved Gables of Willemstad, 2014, photographs author. Clockwise from top left: Breedestraat 37, Heerenstraat 29–31, Handelskade 3, and Pietermaaiweg 16.

- Figure 5.11: Details of Breedestraat 3–5, Willemstad. From left: ca. 1890, photograph Soublette et Fils (Collection Nationaal Museum van Wereldkulturen, Netherlands. Coll.nr. TM-60028736); ca. 1890–1895, photograph Soublette et Fils (Thomas Frederick Davi

- Figure 5.12: Breedestraat in Otrobanda, 1895–1900, photograph Soublette et Fils. Thomas Frederick Davis papers, Descriptive account of Curaçao, Netherlands Antilles, 1902, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, USA. mm 80003197.

- Figure 5.13: Breedestraat 24. Left: unknown photographer, detail, 1945–1960 (Collection Nationaal Museum van Wereldkulturen, Netherlands. Coll.nr. TM-60060876). Right: 2014 (photograph author).

- Figure 5.14: Handelskade 6, details. From left: 1888, photograph Soublette et Fils (Leiden University Library, Netherlands, Digital Collections. KITLV 5325); 1954, photograph H. van der Wal (Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed, Netherlands, Collectie T

- Figure 5.15: Renaissance Hotel, Willemstad. 2014. Photograph author.

- Figure 5.16: Brionplein, Willemstad. 2014. Photograph author.

- Figure 6.1: Van Vleck Hall, Hope College, Holland Michigan, built 1857. Photograph, ca. 1859. Holland, MI, USA, Joint Archives of Holland, Photograph Collection. H88-PH5470.

- Figure 6.2: Lubbers Hall, Hope College, Holland Michigan, built 1942. Undated photograph. Holland, MI, USA, Joint Archives of Holland, Photograph Collection. H88-PH5260-008.

- Graphs

- Graph 3.1: Volume of pepper imported by Dutch East India Company, for years in which entire fleet is known to author. Source: author; see Table 3.1 for data.

- Graph 3.2: Estimated volume of pepper imported by Dutch East India Company in the seventeenth century. Source: author; see Table 3.2 for data.

- Tables

- Table 3.1 Volume of pepper imported by Dutch East India Company, for years in which entire fleet is known to author. Sources: Hollandse Mercurius and Cargo Lists in Nationaal Archief, The Hague, Archief van Johannes Hudde (1628–1704), archive nr. 1.10.48,

- Table 3.2 Estimated volume of pepper imported by Dutch East India Company in the seventeenth century. Sources: Hollandse Mercurius and Cargo Lists in Nationaal Archief, The Hague, Archief van Johannes Hudde (1628–1704), archive nr. 1.10.48, inventory nr.