What can space tell us about our past? Which stories do memory sites narrate? Which memories do they transmit? And, more importantly, how can we read their meanings? Semiotics can provide us with a homogeneous, shareable and theoretically sound methodology to analyse space within a comparable and common frame of reference for scholars of memory studies and traumatic heritage, as well as for historians, architects and museum curators. The book describes in clear and understandable language the main semiotic concepts that can be used to analyse space, illustrating them with carefully chosen case studies of memory spaces – monuments, museums, post-war urban restoration, filmed and virtual space – in order to show the applicability and efficacy of a semiotic methodology.

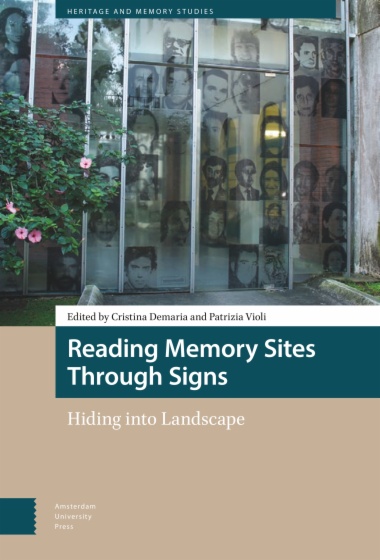

- Cover

- Table of Contents

- For a Semiotics of Spaces of Memories

- Practices of Enunciation and Narratives from Monuments to Global Landscapes of Inheritance

- Cristina Demaria and Patrizia Violi

- 1 Stories that Shape Spatialities

- Lieu and Milieu de Mémoire through the Lens of Narrativity

- 2 Interpretation and Use of Memory

- How Practices Can Change the Meanings of Monuments

- 3 Uncomfortable Memories of Fascist Italy

- The Case of Bigio of Brescia

- 4 What Does Fascist Architecture Still Have to Tell Us?

- Preservation of Contested Heritage as a Strategy of Re-Enunciation and ‘Voice Remodulation’

- 5 Berlin, the Jewish Museum and the Holocaust Memorial

- 6 Making Space for Memory

- Collective Enunciation in the Provincial Memory Archive of Córdoba, Argentina

- 7 Ruins of War

- The Green Sea and the Mysterious Island

- 8 Turning Spaces of Memory into Memoryscapes

- Cinema as Counter-Monument in Jonathan Perel’s El Predio and Tabula Rasa

- 9 Voices from the Past: Memories in a Digital Space

- The Case of AppRecuerdos in Santiago, Chile

- 10 500,000 Dirhams in Scandinavia, from Mobile Silver to Land Rent

- Index

- Index of Names

- List of Illustrations

- Figure 2.1 The Affile monument in honour of Rodolfo Graziani. Still from the documentary ‘If Only I Were That Warrior’ (2015) directed by Valerio Ciriaci and produced by Awen Films

- Figure 3.1 The Bigio sculpture

- Figure 3.2 Mimmo Paladino’s stele

- Figure 4.1 Enunciational projection of the ideological subject in Fascist architecture. The rectangle represents the architecture considered as enunciated discourse (AT: architecture as text), while the circle is the subject of enunciation (S), that is p

- Figure 4.2 The Middle Finger (amputated Roman salute) directed against the Palazzo Mezzanotte in Milan

- Figure 4.3 The former OND building today. It is now a university museum

- Figure 4.4 Lowering the ideological voice of the architecture: while the enunciational marks that manifested the Fascist subject of enunciation are cancelled, the refurbishment does not project an explicit subject

- Figure 4.5 A picture of exGIL (now WeGIL) building

- Figure 4.6 Re-tuning the voice of ideological architecture: the new subject of enunciation, which is represented even in the renaming of the building (WeGIL), partially overlaps (at least aesthetically) with the simulacrum of the fascist subject of enunc

- Figure 4.7 Critical distance from the ideological voice: the patina is preserved to mark the status of the monument as historical trace and document

- Figure 4.8 Distancing the ideological voice through enunciational encasing: the old enunciational structure is ‘put in quotes’ in the new text, in which the new subject does not speak in first person

- Figure 4.9 The illuminated quote by Arendt superimposed on the bas relief

- Figure 4.10 New text with a new manifested enunciational subject, that projects itself onto the previous text, disputing the previous voice

- Figure 5.1 The Jewish Museum, plan of the underground itineraries

- Figure 5.2 The Jewish Museum, cross-section of the building

- Figure 6.1 The outside of the museum, Thursday, 30 June 2016, with a photographic exhibition on the left

- Figure 6.2 One of the patios

- Figure 6.3 Patio with the cells

- Figure 7.1 Palermo, a postcard from 1935: the sea waves almost reach the city

- Figure 7.2 An image from the 1930s: the balustrade of the Foro Italico seafront is featured on a postcard from the early twentieth century

- Figure 7.3 Francesco Laurana, Bust of Eleanor of Aragon, 1471, Palermo,

Palazzo Abatellis

- Figure 7.4 The rows of princesses run along the edges of the pavement, suggesting a second threshold between the road and the park

- Figure 7.5 A ship sailing the sea’s green waters

- Figure 7.6 The same photo, now an indulgent cliché of the city, is used on the cover of a book listing the amusing oddities of Palermo

- Figure 7.7 René Magritte, La Représentation (1937)

- Figure 10.1 Dirhams found in the hoard of Stora Velinge (Gotland Island, Sweden), with a silver arm ring (after Stenberger 1947)

- Figure 10.2 Distribution of dirham hoards in relation with Scandinavian activity, eighth to eleventh centuries. Note the concentration on the south-eastern coasts of today’s Sweden, along the Baltic coast and the rivers of the drainage basins of the Balt

- Figure 10.3 Distribution of minting places emitting dirhams (after Kilger 2008)

- Figure 10.4 Map of Jutland peninsula constriction with position of Danevirke sections (after Tummuscheit and Witte 2019)

- Figure 10.5 �Map of Danevirke segments with the positions of Hedeby and Shlesvig cities (after Tummuscheit and Witte 2019)