In 1680, the poor cottager Mary Herring gave birth to conjoined twins. At two weeks of age, they were kidnapped to be shown for money, and their deaths shortly thereafter gave rise to a four-year legal battle over ownership and income. The Herring twins’ microhistory weaves throughout this book, as the chapter structure alternates between the family’s ordeal and the broader cultural context of how so-called ‘monstrous births’ (a contemporary term for deformed humans and animals) were discussed in cheap print, exhibited in London’s pubs and coffeehouses, examined by the Royal Society, portrayed in visual culture, and litigated in London’s legal courts. This book ties together social and medical history, Disability Studies, and Monster Studies to argue that people discussed unusual bodies in early modern England because they provided newsworthy entertainment, revealed the will of God, and demonstrated the internal workings of Nature.

- Cover

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Dedication

- Conventions and Abbreviations

- Preface. A Note about Form

- Étude 1. An Anomalous Birth

- Chapter 1. Introduction: Monstrosity, Disability, and Knowledge

- Étude 2. A Newsworthy Event

- Chapter 2. Monstrous Print

- Étude 3. A Popular Attraction

- Chapter 3. Monstrous Shows

- Étude 4. The Expert Visitor

- Chapter 4. The Royal Society

- Collection and Dissemination

- A Natural History of the World

- Étude 5. A Decorative Commodity

- Chapter 5. Visual Culture

- Woodcuts

- Engravings

- Painted Portraits

- Étude 6. The Lawsuit

- Chapter 6. Conclusion: Autonomy, Agency, and Unfree Labour

- Appendix 1: James Paris du Plessis’s Biography

- Appendix 2: Agreement between Henry Walrond and Richard Herring

- Bibliographical Abbreviations

- Primary Sources: Archival

- Primary Sources: Printed, Visual, Material, Modern Editions

- Secondary Sources

- Index

- List of Figures, Maps, and Tables

- Figures

- Figure 1. Aquila and Priscilla Herring were erroneously depicted as joined back-to-back in this woodcut. A True Relation of a Monstrous Female-Child, with Two Heads, Fower Eyes, Fower Ears, Two Noses, Two Mouthes, and Fower Arms, Fower Legs, and All Thing

- Figure 2. Artist’s conception of Priscilla and Aquila Herring, based on Andrew Paschall’s description of their anatomy (see Étude 4). © Lisa Temple-Cox, 2019.

- Figure 3. A hand-coloured broadside depicting conjoined piglets. This copy, from the British Museum, features the original German descriptions (above the front and back views of the piglets), but the original imprint (‘Niclas Meldeman Brieffmaler’,46 whic

- Figure 4. England’s earliest-surviving piece of monstrous print, featuring conjoined twins born in Middleton Stoney, Oxfordshire in 1552. The handwritten notes between the woodcuts indicate that the twins died at two weeks old, perhaps, as John Seller lat

- Figure 5. Henry Bynneman’s illustration of the Middleton Stoney twins, printed from a woodblock originally owned by Jacques Macé and imported from Paris, which appeared in Bynneman’s English editions of both Pierre Boaistuau’s Certaine Secrete Wonders of

- Figure 6. The final page of the probated will of John Fulwood the Younger, decorated with sketches of ‘prodigies’ born and mentioned in print in 1562 (compare to Figures 7, 8, and 9). At least some of the illustrations must have been added after the will

- Figure 7. Illustrations from the broadside The Shape of .II. Mõsters, written by William Fulwood, which resemble the third and fourth sketches surrounding John Fulwood the Younger’s will (compare to Figure 6). Only the right image was described in the bro

- Figure 8. The illustrator of John Fulwood the Younger’s will was demonstrably a consumer of monstrous print, as both this infant and that depicted in Figure 9 were copied directly into the margins around the probated will (see Figure 6). The True Reporte

- Figure 9. Every feature of this woodcut, from the umbilical cord to the notch on the right ear, was reproduced in the margin of John Fulwood the Younger’s probated will (see Figure 6). John D., A Discription of a Monstrous Chylde, Borne at Chychester in S

- Figure 10. This young man with ‘Bristles like a Hedge-hog’ all over his body was to be seen at ‘ye horsegrom in theobalds Row’ by ‘Red Lyon Squar’. Leaving a blank for the location of an exhibition to be added by hand implies that the show might not have

- Figure 11. James Paris du Plessis’s scribbles (in the margins) versus the scribe’s clear and careful script. This depiction of the dwarf John Grimes is the sole illustration in Sloane MS 3253. James Paris Du Plessis, Servant to Samuel Pepys: Collection of

- Figure 12. The clearly fictional ‘Tartar’ archer, as both an etching (left, inserted into Paris’s manuscript) and a painting. While it is obvious where the artist got inspiration for the illustration, it is less clear why Paris preserved the original prin

- Figure 13. Martha and Mary Waterman, conjoined twins born in Fisherton Anger, Wiltshire in 1664, pictured from the front, the back, and during dissection; these pen-and-ink sketches accompanied Roger Baskett’s letter to the Royal Society. While obviously

- Figure 14. An unusual example of an etching inserted into A Short History, this image depicts the wet preserve of a pair of conjoined twins owned by the Italian Count Moscardo. James Paris Du Plessis, Servant to Samuel Pepys: A Short History of Human Prod

- Figure 15. The monstrous head of a colt preserved by Robert Boyle and dissected by Robert Hooke. The letters visible on the eye and forehead correspond to the article’s description: ‘It had four Eye-browes, placed in the manner exprest […] by aa, bb; aa r

- Figure 16. The partial skull in this etching (left), supposedly belonging to a human giant, had periodically been described in the Philosophical Transactions since the seventeenth century.29 By comparison, the infant described and sketched (right) by Timo

- Figure 17. When the article about the Hungarian conjoined twins Helen and Judith appeared in the Philosophical Transactions, it was accompanied by two new etchings by James Mynde, both of which had been copied from earlier prints. The article’s second ima

- Figure 18. The Angolan’s external genitalia, from Parsons’s book. The dense linework over the entire image clearly depicts dark skin. James Parsons, A Mechanical and Critical Enquiry into the Nature of Hermaphrodites (London, 1741), Tab. I.; Wellcome Coll

- Figure 19. The Angolan’s genitalia (centre), with views of Constantia Boon’s genitals juxtaposed on either inner thigh. The close cross-hatching of the middle illustration denotes a darker skin colour than the images on either side, whose labia/bifurcated

- Figure 20. The Herring twins, depicted as joined at the side, carved into a red clay plate inscribed with the initials IO and SD and their year of birth (1680). As a result of their appearance in Andrew Paschall’s account of the 1685 rebellion, in which h

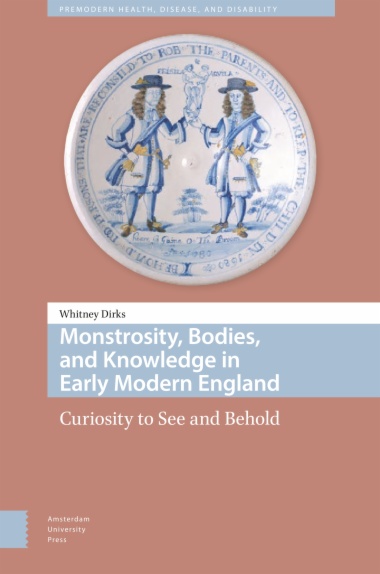

- Figure 21. Aquila and Priscilla Herring, depicted as joined between the breasts, being held aloft by their alleged kidnappers, Henry Walrond and Sir Edward Phelips (see Étude 6). Dish: Earthenware Tin-Glazed Pale Duck-Egg Blue on Both Sides, and Painted o

- Figure 22. Priscilla and Aquila Herring, reversed from their depictions on the Fitzwilliam’s plate (see Figure 21); this plate also features the date (written twice). The glaze is noticeably different between the two plates: the blue-and-white of Cardiff’

- Figure 23. This print purports to have been ‘drawn and published by [the pig-faced lady’s] late attendant’, presumably the maid carrying a steaming silver trough to the right of the table. Many hog-faced etchings were produced along with this one in 1815

- Figure 24. The printer paired a new woodcut (right) of the ‘monsterous Chylde / Borne in the Ile of Wight’ with an existing block depicting an infant in order to tell the story of these twins born in 1564. John Barker, The True Description of a Monsterous

- Figure 25. Illustrations of the pig-faced gentlewoman with two of her suitors, from The Long-Nos’d Lass. While the image of the lady would almost certainly have been created expressly for this ballad, the men she was paired with were clearly extant woodbl

- Figure 26. An illustration of the pig-faced lady and one of her suitors (left), and the same printing block, altered to adorn a different pamphlet (right).15 The upper left corner of the block was removed and replaced, which is clearly visible as a white

- Figure 27. The original block depicting front and back views of a girl born with loose, ruff-like folds of skin. H.B., The True Discripcion of a Childe with Ruffes, Borne in the Parish of Micheham, in the Cou[n]tie of Surrey (London, 20 August 1566), sing

- Figure 28. Note the wavering line along the infant’s shoulders (left), where the ‘ruffes’ from Figure 27 were cut away. The excess skin around the hips was maintained, perhaps because, when divorced from its original context, the remaining folds resemble

- Figure 29. The tallest (William Evans), shortest (Jeffrey Hudson), and oldest (Thomas Parr) men ‘of this age’ (the 1630s). This page was printed twice, once for the typeface and a second time for the engraving. [Thomas Heywood and George Glover], The Thre

- Figure 30. In this etching, the pig-faced lady attempts to fend off a number of stereotyped suitors. George Cruikshank, Suitors to the Pig Faced Lady / Every Man to His Taste ([London], 22 March 1815), single page; Library of Congress.

- Figure 31. The pig-faced lady, opposite ‘The Spanish Mule of Madrid’ (King Ferdinand VII of Spain). No other hog-faced etching pairs the lady with another individual in this manner, though the famous corpulent men Daniel Lambert and Edward Bright were dep

- Figure 32. Jeffrey Hudson and the monkey Pug, both members of Queen Henrietta Maria’s menagerie, with their royal mistress. Anthony van Dyck, Queen Henrietta Maria with Sir Jeffrey Hudson (1633);73 courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. (CC0).

- Figure 33. This etching of the miniaturist Richard Gibson and his wife Anne (née Sheppard), dwarfs in the courts of King Charles I and Queen Henrietta Maria respectively, closely resembles Peter Lely’s multiple portraits of Gibson. Sheppard’s depiction, o

- Maps

- Map 1. Geographical distribution of the 77 pairs of conjoined twins described in Table 1. © Sebastian Ballard 2019.

- Map 2. The locations at which human and animal curiosities, alive and dead, could be seen in late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century London, based on the Collection of 77 Advertisements Relating to Dwarfs, Giants, and Other Monsters and Curiosities

- Map 3. The home parishes of the deponents in Herring v. Walrond, all of whom viewed Priscilla and Aquila Herring. The closest witnesses lived in Isle Brewers itself, while others came from as far away as Burton in the northwest (23 miles, or 37 km, distan

- Tables

- Table 1. Conjoined Twins in Early Modern Europe

- Table 2. Remarkable Humans and Animals in the Philosophical Transactions

- Table 3. Herring v. Walrond Witnesses