A headman of a remote Kelabit longhouse in Borneo is wrestling with recent changes caused by logging and roadbuilding. During this time of tension, he tells three historical narratives defining what makes the good life. His stories of history celebrate pioneering heroes who led through warfare and migrations, who interact with the Brooke state and initiate peace-making, and who journey to seek local Christian missionaries. This microhistory highlights the resilience of values in the face of transformative change, values providing a cultural structure for the Kelabit to redefine and adapt whilst maintaining their identity as a community.

This work is relevant to Austronesian studies, Southeast Asian history, oral history, the anthropology of value, sociality and ethnic identity, Christian conversion, and issues of borderlands, decolonization, and indigeneity. It is of interest to readers concerned with the history of transnational peoples of Borneo, including the Kelabit, Sa’ban, Kenyah, Ngurek, Penan, and the Lun Dayeh.

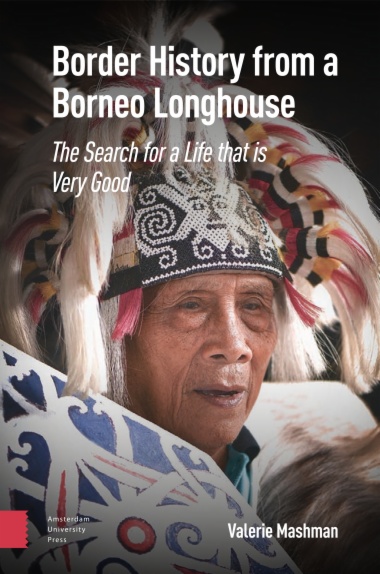

- Cover

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction

- 1.1 Introduction

- 1.2 The Austronesian setting

- 1.3 What the narratives are about

- 1.4 Questions raised by these histories

- 1.5 Minority indigenous history matters

- 1.6 Outline of the book

- 2 The Longhouse and Connections Across Borders

- 2.1 Introduction

- 2.2 Location of Long Peluan: Connections across borders and the world beyond

- 2.3 Long Peluan and its neighbours

- 2.4 Recent changes: Logging and after

- 2.5 The longhouse settlement

- 2.6 Population and ethnic composition

- 2.7 Education

- 2.8 Subsistence

- 2.9 Padi farming

- 2.10 Institutional systems in the village

- 2.11 The origins of Long Peluan: Pa’ Di’it

- 2.12 The last hundred years and the story of Long Peluan

- 2.13 The Krayan, Sa’ban, and Kelabit as Lun Tauh “Our People”

- 2.14 The Ngurek as Lun Tauh “Our People”

- 2.15 Deeper history and secondary burial

- 2.16 The signs of early settlement in Long Peluan: Ngurek and Kelabit

- 2.17 Megalithic stone mounds and stone graves

- 2.18 Conclusion

- 3 Oral Narratives and Underlying Values

- 3.1 Introduction

- 3.2 Defining oral historical narratives

- 3.3 Characteristics of historical oral narratives: genealogies

- 3.4 Characteristics of historical oral narratives: The narrator

- 3.5 Characteristics of historical oral narratives: Place

- 3.6 Characteristics of historical oral narratives: Episodic time

- 3.7 Characteristics of historical oral narratives: Meanings and the narrator

- 3.8 The Kelabit idea of value: Doo’

- 3.9 The meaning of doo’ the Kelabit value and the adet

- 3.10 Rice cultivation, food, and prestige

- 3.11 Value, sociality, and our people

- 3.12 Conclusion

- 4 Methods for Researching the Narratives

- 4.1 Introduction

- 4.2 The role of anthropology in the utilization of oral history

- 4.3 The chain of transmission and the narrator’s message

- 4.4 Concepts of time

- 4.5 Multiple viewpoints

- 4.6 Transcribing and translating

- 4.7 Thoughts on the process of ethnographic fieldwork

- 4.8 The position of the anthropologist

- 4.9 Ethics in anthropology

- 4.10 Method: Multi-sited fieldwork

- 4.11 Conclusion

- 5 Warfare and the Migrations of Our People

- 5.1 Introduction

- 5.2 Summary of the first narrative

- 5.3 Translation and commentary of the first narrative

- 5.4 Discussion: Lun Tauh “Our People” in the first narrative

- 5.5 Conclusion

- 6 The Search for the “Life of Government”

- 6.1 Introduction to the second narrative

- 6.2 Summary of the narrative

- 6.3 Translation and commentary of the second narrative

- 6.4 Discussion: How the narrator makes meaning

- 6.5 Conclusion

- 7 The Beginning of “The Life of Prayer”

- 7.1 Introduction

- 7.2 Summary of the narrative

- 7.3 Translation and commentary of the third narrative

- 7.4 Discussion: A mission tale – conversion and continuity

- 7.5 Conclusion

- 8 Conclusion

- 8.1 Introduction

- 8.2 Setting and methods for the “Stories of History”

- 8.3 The first narrative: The meaning of lun tauh

- 8.4 The second narrative: The quest for ulun perintah – “the life of government”

- 8.5 The beginning of “a new life that is very very good”

- 8.6 Closing remarks

- Appendices

- Index

- List of Figures

- Frontispiece: Tama Pasang Murang, later known as Melian Tepun, the headman who inspired narrator Melian Tepun to take on his name. Photograph taken in 1971. Nicholas Kusing Nga’ang.

- Figure 1.1: So Tepun, father of Melian Tepun, inside his kitchen, November 1984. Valerie Mashman.

- Figure 1.2: A megalithic grave at Long Peluan, Menatoh Lem Dusur, 2011. Valerie Mashman.

- Figure 2.1: Map showing places of “our people.” Lee Guan Heng.

- Figure 2.2: Tama Lalo’, a Sa’ban elder getting his boat ready to take the author and family back to Long Peluan. Taken at Marudi, November 1984. Valerie Mashman.

- Figure 2.3: Group climbing the hills back to Long Peluan, November 1984. Remat Murang and Sina Rang, sisters-in law of the author, Sina Eo, descendant of Lian Ajin, and Tama Bulan, descendant of Telen Sang. Note their heavy load of goods. Valerie Mashman.

- Figure 2.4: Narrator Melian Tepun outside his living area, 2012. Valerie Mashman.

- Figure 2.5: Internal view of three family areas of the longhouse. On the right are the family hearths, Long Peluan, 2013. Valerie Mashman.

- Figure 2.6: Fishing in the Long Peluan area, 2011. Osart Jallong.

- Figure 3.1: Preparing meat at a feast in Long Peluan at Melian Tepun’s house, 2013. Valerie Mashman.

- Figure 7.1: Susan Udau resounding the call to Christian prayer using a bamboo gong, Long Banga, 1984. Valerie Mashman.

- Figure 7.2: Melian Tepun and Lake’ Tawan, “We are like brothers,” Long Peluan 2013. Valerie Mashman.