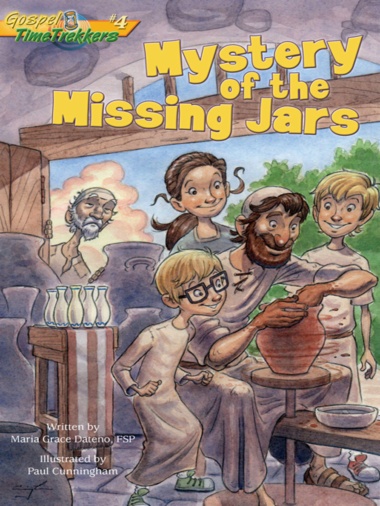

A time-traveling adventure imaginatively retraces Jesus raising Jairus’ daughter, Sarah, from the dead, revealing that “being raised to new life” has more than one meaning!

In this fourth volume of the Gospel Time Trekkers series, children ages 6–9 are taken on a journey that imaginatively retraces Jesus raising Jairus’ daughter, Sarah, from the dead, revealing that “being raised to new life” has more than one meaning!